Rosh Hashanah 5778 Day Two - “We do not enjoy the protection of that country any longer”

September 22, 2017

The Suffolk County jail, in South Boston, looks like a lot of the other buildings around it. The neighborhood is a concrete and brick complex of brutal buildings, neglected parking lots, rutted roads. Lots of warehouses.

Except, of course, that the jail is a warehouse not for property, but people.

You might expect the facility to house violent criminals, thieves, troublemakers. In some cases, undoubtedly, you would be right.

But the Suffolk County jail also rents space to Immigrations and Customs Enforcement.

And so it is that among the lawbreakers and delinquents, there’s also a man named Francisco Rodriguez.

You may know Francisco’s story. Francisco fled his native El Salvador in 2007. Afraid for his life, he came here, to Boston and applied for asylum. And he was turned down. First in 2009, and then on appeal in 2011.

But, in the mean time, he returned for every appointed check-in, every hearing. He married, and his family grew. Taking a job as a janitor at MIT, he became a fixture on campus. He’s a member of the school parent committee — a pillar in his church and community in Chelsea.

But at the moment, none of that matters. In June, when Francisco dutifully showed up at the ICE offices in Burlington, he was informed that he would be returning to El Salvador.

On July 13th, as some of you know, I was asked to speak at a rally on Francisco’s behalf.

But the morning of the rally, he was taken into ICE custody. He’s been held in ICE detention at the Suffolk County jail since then.

Welcome to Francisco’s new reality. And ours.

The rally went on as planned. The speaker who spoke following my remarks was his 10-year-old daughter, Mellanie. Now I’ve spoken plenty of times at rallies. And I’ve spoken on platforms, like this one, with kids — usually b’nai mitzvah kids or students at children’s services.

But I had never spoken at a rally with a 10-year-old. Let alone a weeping 10-year-old whose loving father had been snatched from her that day, by armed men in uniform. It’s not an experience I can adequately describe in words.

In July, I went to see Francisco. After getting the proper permissions, and undergoing the CORI background check, and finding the jail, after surrendering my phone and wallet and ID, I was allowed to visit Francisco.

In the press, Francisco is often identified as a janitor. It is, of course, true. He’s worked as a janitor at MIT, is a member of the service employees union, SEIU, Local 32BJ. But, like many of you, Francisco is an engineer by training — in his case, a mechanical engineer.

Unlike many of you, Francisco decided to leave El Salvador when a colleague at his engineering firm was murdered.

Francisco is also a Bible scholar. As we sat, we conversed of his plight in the context of our shared biblical narratives — the Israelites in Egypt, Joseph in the pit, King David on the run from Saul.

In the midst of the conversation, he paused.

“This country is amazing,” he said. “They brought the Bible over an ocean, brought the Bible to a whole continent.”

“But then,” he said ruefully, “they forgot it.”

Most available evidence indicates that Francisco is right. Read the paper or scan your iPad, and wherever you look you see a land that loves its Bible, but forgets its teachings. A land that forgets the parts about opening your hands to the poor, forgets the parts about paying your workers fairly and promptly, forgets the parts about clothing the naked and feeding the hungry.

A land that forgets the parts, repeated in our Torah no less than 36 times, that say to love and respect the immigrant.

Amazingly, Francisco told me that he doesn’t succumb to despair. He knows, he says, that God will rescue him.

But there are moments when it’s hard — even for a faithful believer like Francisco.

When he speaks on the phone to his children.

He told me that he tries to keep their spirits up. He tells them that everything is fine.

When he speaks to his children, Francisco hides the truth. For their sake.

For our sake, for the sake of our children — for the sake of our souls — we must tell the truth.

Truths like 60% to 70% of farm workers are immigrants, mostly undocumented. Truths like immigrants clothe us, and feed us, and care for us and our children. Truths like our entire economy is built on immigrant labor. Truths like, since the inauguration, there has been a 156% increase in the detention of immigrants with no criminal history.

Truths like treating hard-working, law abiding neighbors in such a way is nothing less than a national disgrace.

Truths like, as a Jewish community, we know this intuitively, because this story is a Jewish story.

This picture shows my family’s path to citizenship. Way in the back on the right, is my great Aunt Rose, sitting with her Jewish sisters in a textile factory, an immigrant garment worker. She, my grandmother, and their brothers and sisters, toiled every day to put clothing on the back of Americans.

Why? Because this country held out the promise of a paycheck, the promise of freedom from Jew-haters in Europe.

And the promise of a new home.

This new home, this new country, had a statue in a harbor, welcoming immigrants. It rang a loud and clear bell for freedom, for liberty.

I’m not talking about a symbolic bell – I’m talking a real bell! It was called the Liberty Bell!

It even had a quote from the Jewish people’s Torah on it:

Ukratem dror ba’aretz, l’chol yoshveha.

“Proclaim liberty throughout the land, unto all the inhabitants in it.”[1]

What is this dror, the call for liberty cast in the very metal of this old bell?

Liberty means a lot of things to a lot of people.

But the Jewish definition of liberty, of dror, is specific.

In the Talmud — in tractate Rosh haShanah in fact — Rabbi Yehudah asks, “What is the significance of the word dror?” And he answers, “[It refers to] a person who can medayyer, who can live wherever they want, and do their business in the whole country.[2]

Freedom of movement. Of course that would be the Jewish definition of liberty. The immigrant experience is part of the Jewish DNA.

Jews know, in our guts, what it means to be on the move — or on the run. To search, to scrimp, to scrap, to start over, to march off the edge of the map.

It’s in our very name. The word in Hebrew for “Hebrew” is Ivri. It literally means “boundary-crosser.” “Border crosser.”

The foundation story of our people is an immigrant story, the Exodus from Egypt. Read it with this consciousness, and you see — it’s all there. An immigrant group, perhaps the first guest-workers in recorded history – oppressed, underpaid, vilified – forced to labor under the most brutal of conditions.

Today, folks like Francisco who know their bible know how the story ends. The despised immigrant prevails over Pharaoh.

The Exodus story shakes us from our complacency, reminding us that God cares deeply about even the least powerful. Especially the least powerful. Reminding us that God pays attention to how we treat them. Reminding us that God takes note.

And if God takes note of the lowly Israelites, surely God still takes note today.

When we ignore the discrimination perpetrated against our immigrant neighbors, God takes note.

When, in Los Angeles, Romulo Avelica-Gonzales is taken into ICE custody — in front of his 13-year-old daughter, as he drops her off at school — God takes note.

When a man like Shoeb Baba escapes government thugs in Bangladesh, seeking asylum in the United States, turning himself over to US authorities at the border — only to be trapped in ICE detention for over two years — God takes note.

When Oscar and Irma Sanchez are arrested, in a Texas hospital, awaiting surgery for their infant son Isaac — God takes note.

When ICE shuffles thousands of detainees throughout a web of private prisons and county jails for months and years at a time —

You can be sure. God takes note.

This moment calls to the Jewish people — now as always an immigrant people, a nation of border-crossers — to refuse and resist.

Of course, you may be saying to yourself, “that’s all well and good, rabbi, but my ancestors came here legally. They immigrated the right way.”

And it is true that, a century ago, the United States welcomed millions of immigrants, including millions of Jewish immigrants. Including my ancestors.

And, perhaps, yours.

Jewish immigrants who came to this country and built lives and homes and corner stores and raised PhD’s and Orthodontists and English teachers — big beautiful families at big beautiful tables, filled with platters of gefilte fish and delightfully dense matzah balls and boxy bottles of Manischewitz.

A funny thing, though, about that Manischewitz. The kosher food empire we now know and (ahem) “love” began with a rabbi named Dov Behr, a kosher slaughterer who started a matzah factory in Cincinnati in the late nineteenth century.

Of course, Rabbi Manischewitz wasn’t born a rabbi. But as it turns out, he wasn’t born a “Manischewitz” either.

His surname in his native Lithuania was “Abramson.” Nobody knows for sure, but family rumor has it that Rabbi Dov Baer Abramson purchased the passport of a dead man to gain passage to America in 1888.

A man named Manischewitz.

Whether it’s escaping thugs in El Salvador or Cossacks in Lithuania, people tend to do whatever’s necessary to safeguard themselves and their families. Like leaving everything they know. Like coming to a new country to make a new life.

Whether or not it happens to be “legal,” at the time you happen to be running from Cossacks — you do what you have to.

Maybe, if you have the money, you pay off a border guard.

Maybe you steal a dead man’s name to make a new life.

Our families did what they had to. Because the alternative was unthinkable.

Listen to the words of this letter, written in 1908 to Israel Zangwil, a British Jew who headed up the Jewish Territorial Organization, from Alter Perling — a self-described “homeless wanderer, a true wandering Jew:”

I'm far from home — Perling writes — the Jewish ghetto in Russia. I've been thrown out of Berlin and Koenigsburg many times and finally, with great difficulty, I obtained a ship ticket from one of my cousins in New York...

If I were to be sent back from America I would be devastated. I can never go back to Russia, and it is impossible for me to remain in Germany.

Then the only option left for me would be to jump off a bridge.

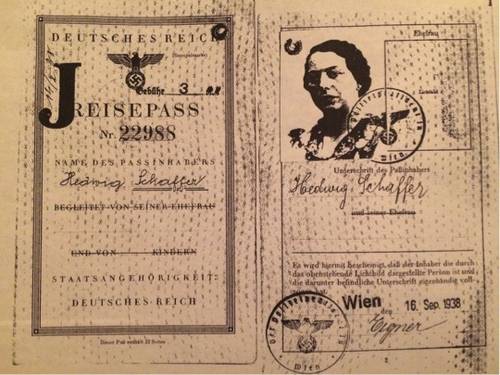

Or consider our own George Schaffer. I was blessed to share a meal with George and Carolee in their beautiful home. George was kind enough to show me some documents from his incredible journey from Europe to this country.

In particular, I was struck by a peculiar form George showed me.

His had it prepared in England, where they had escaped to from Vienna. Escaped, because why would Jews stay in a place where all your documents must be stamped with a big “J”?

It’s called, if you can imagine such a thing, an “Affidavit of Identity.”

George doesn’t have to imagine.

The document reads: “I, Hedwig Schaffer… and my son Georg Heinz, born Vienna [February 12, 1900 and March 19, 1928], do hereby declare that [we are] nationals of Germany (Austria)…

We are unable to obtain a valid passport from the Government to which we legally owe our allegiance, for the following reasons:”

And the reason they list?

“Because we do not enjoy the protection of that country any longer.”

When we hear the stories of immigrants faced with the prospect of being torn from their homes in this country, when we read heart-wrenching stories of our neighbors forcibly returned to Mexico and Guatemala and Haiti and El Salvador — we as Jews can’t help of think of Alter Perling, and the millions of Jews like him.

We as Jews can’t help but think of Hedwig and George Schaffer.

It’s why Jewish representatives take to the House floor to speak on behalf of the virtues of our immigrant neighbors. Like the Jewish congressman from New York who rightly reminded opponents of immigration that if they “had their way, and we awoke one fine morning and found all our population of foreign origin had departed… there would be no rolls for breakfast, no sugar for the coffee, and no meat for dinner — for practically all workers in” food service are immigrants.

But the Jewish congressman who argued so passionately on behalf of immigration is not currently in the House. His name is Emanuel Cellar. And he didn’t offer his remarks this year. Or last year.

He made those remarks over 90 years ago.

And the reason Cellar took to the House floor was because of the legislation then before the US House of Representatives. It would come to be known as the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924. And it imposed a strict immigration quota system that kept the door wide open to immigrants from Western and Northern Europe — but severely limited immigration from Eastern Europe, and all but eliminated immigration from Asia and Africa.

Which meant that, in the years between 1933 and 1945, when European Jews desperately needed a place of refuge, a place to escape the Nazi murder machine, this country was mostly closed to them.

Because, unlike the generation of legal immigrants that came before them — like my family, and maybe yours — the same group of people with the same lineage was now classified as “illegal immigrants.”

As Jews, we are not fooled by sleazy rhetoric. The line — between what is legal and illegal — is not immutable. It is not set in stone. It is an arbitrary line created by human authorities.

We know it’s arbitrary because, for centuries, that line was drawn across our backs.

One day, you’re welcome. And the next day — in the words of George’s affidavit of identity — the country to which you “legally owe your allegiance” declares you illegal.

And make no mistake: where you fall on the line between legal and illegal depends, more often than not, on what you look like and what language you speak.

To today’s US government, a Muslim name or a Latino accent calls your humanity into question. But in the 30s and 40s, when Jewish blood flowed in the streets of Europe, it was a Jewish name and Yiddish accent that made you undesirable.

Cellar made it his life’s work to overturn the state-sanctioned cruelty of the Johnson-Reed Act. And in 1965, over 40 years after Johnson-Reed was passed, the US Congress passed the Hart-Celler Act, named in part after Emanuel Cellar. It abolished quotas based on national origin, stating:

"no person shall … be discriminated against in the issuance of an immigrant visa because of the person's race, sex, nationality, place of birth, or place of residence."

Little would Emanuel Cellar know that in the year 2017, when a new president would sign Executive Order 13769, halting immigration from seven majority-Muslim nations, it would be immediately challenged in court — based, in large part, on the clause from his law, the Hart-Cellar Act, that I just quoted.

In 1965, standing at the foot of the Statue of Liberty as he signed the bill, President Johnson said it would "repair a very deep and painful flaw in the fabric of American justice.”

But today the forces of hate and ignorance and intolerance look to tear the fabric anew, to tear children from parents, to tear parents from children. To tear students from their classrooms and soldiers from their battalions. To tear communities apart, house to house, neighbor from neighbor.

For some of us, these neighbors exist as an abstraction, a farm worker in a field, a friendly gardener, maybe a restaurant worker we glimpse from behind a kitchen door, forgotten when the door swings closed.

But for others, these immigrant neighbors are not abstractions. Many of you know that we were blessed to welcome a group of Muslims from Uganda to our sanctuary and our social hall this July. They didn’t come to us by random happenstance.

We are bonded with this community through Michael Biales and Sarah Coletti. And through Michael and Sarah’s son, Adam. Adam, you may know, has developmental disabilities. He lives in a group home very close to where Anthony and I live, in Concord. He lives in a house of safety and good food and lots of love. Because it is run by an amazing man, a man of extraordinary integrity and kindness.

A Muslim man, an immigrant from Uganda.

He makes sure Adam and his housemates are safe and protected.

His name is Isaac. If it weren’t for Isaac, Michael and Sarah would not be so confident that Adam is getting the care and attention he needs.

We stand in solidarity with Isaac and his community because our tradition calls us to do so. And so does theirs. On that day in July, Isaac’s sheikh, Rajab Mayanja, stood here, on this bimah in this spot. He taught:

"Allah teaches that you must work together with the people who are not against you,” the sheikh instructed. “Who don't fight you. You must work together."

I’ve mentioned to you that the Talmud teaches that “four things reverse our fate. Tz'akah — crying out; Tzedakah— repairing injustice; Shinui HaShem — a change of name, and Shinui Ma'aseh — a change of action.”

The word Tzedakah, as you may know, comes from the word Tzedek — justice. The proof text the Torah gives for Tzedakah’s power comes from Proverbs: Tzedakah tatzil mi’mavet. “Justice rescues from death.”

This day, we are called to work together for justice.

Not only to rescue the millions of immigrants currently endangered by deportation squads run wild.

But to rescue members of our communities, this community, like Adam — whose very life and well-being depend on the labor of immigrants like Isaac.

And so I ask you — write a letter to our state and national officials, asking them to free Francisco. Or write a letter to Francisco.

Come to the joint Brotherhood-Na’aseh breakfast, Sunday October 1st, and hear from Acton police about their policy refusing to submit arrest records to ICE officials. Hear from our Senator, Jamie Eldridge, about the Safe Communities Act, a law that would keep ICE officials away from Massachusetts immigrant residents like Fransciso and Isaac.

And finally, a little good news. Isaac, as it turns out, is one of the lucky ones. Sarah wrote me a few weeks ago to tell me he finally received his green card. He started the process when it was more likely for young men like Isaac to be given safe haven in this country. But it was a close call.

On a day when our Torah portion is about another young man named Isaac — another Isaac who faces catastrophe on the altar of zealotry, another Isaac who survives too close a call — let’s commit ourselves, here and now, you and me —

No more.

No more horror in the eyes of young men on the knife’s edge of an uncertain future. No more young people facing tomorrows of terror. No more.

No more children sacrificed on altars, whether altars of fanaticism or bigotry. No more children baffled by countries that declare arbitrary deadlines on their dreams.

Whether in Lithuania or El Salvador, Uganda or Vienna, Brooklyn or Boston. No more.

No more children who live in the shadow of terrible truths, truths their parents struggle to hide from them.

Like in our Torah, this morning. “I see the fire and the wood,” Isaac says to Abraham, “but where is the lamb for a burnt-offering?” And Abraham replies, “God will provide the lamb.”

Does Abraham really believe that? Does he really think God will provide the lamb? Or is he in fact walking in fear of what awaits atop Mount Moriah?

Is he like Francisco Rodriguez, talking on the telephone to his kids, from an ICE detention cell in the Suffolk County Jail in South Boston, telling a fib to keep their spirits up? Telling them everything is fine. Hiding the truth. For their sake.

“God will provide.”

God made a prophet of Abraham. The ram caught in the thicket saved Isaac.

And what about Francisco? Will God provide for Francisco and his children? Will God provide for the dreamers and the detainees, for the day-laborers and refugees? For our neighbors, our caretakers and classmates? On this day? And the next?

Will the promise of the Liberty Bell be fulfilled? Or the Torah’s promise that God’s people will love the immigrant, will respect the stranger?

Or the promise made to the huddled masses, all those years ago in New York harbor, still today, the promise of the mighty woman with a torch, crying with silent lips to the tired and the poor, the tempest tossed, yearning to breathe free, the promise of Lady Liberty, lifting her lamp beside the golden door?

On this day — before the golden door now opening to our new year — the answer to all these questions… they’re up to us.

___________________________________________________________________

[1] Leviticus 25:10

[2] Talmud, Rosh haShanah 9b

Update this content.